A constant arrival. On the work of Valentina Alvarado Matos and Carlos Vásquez Méndez

by Eliel Jones

It has long been said that when a person is about to die, their life flashes before their eyes in a series of images. From Plato to Vanilla Sky, this relationship between images and end-of-life experiences has been a recurring visual and conceptual trope in art, literature and film. Known as the ‘life review’ phenomena and associated with the narrative and cinematographic technique of the “flashback”, these scenes depict significant moments in a character’s history. In mainstream cinema, more often than not, the flashing images provide a sanitised version of the person’s life story; one that is overtly happy and riddled with themes of birth, renewal and fulfilment. In this way, a life review as we have seen through films always reduces human experience to selective memories, creating an overall sense of completion of a supposed “good life”—a life that, according to these images, was well lived.

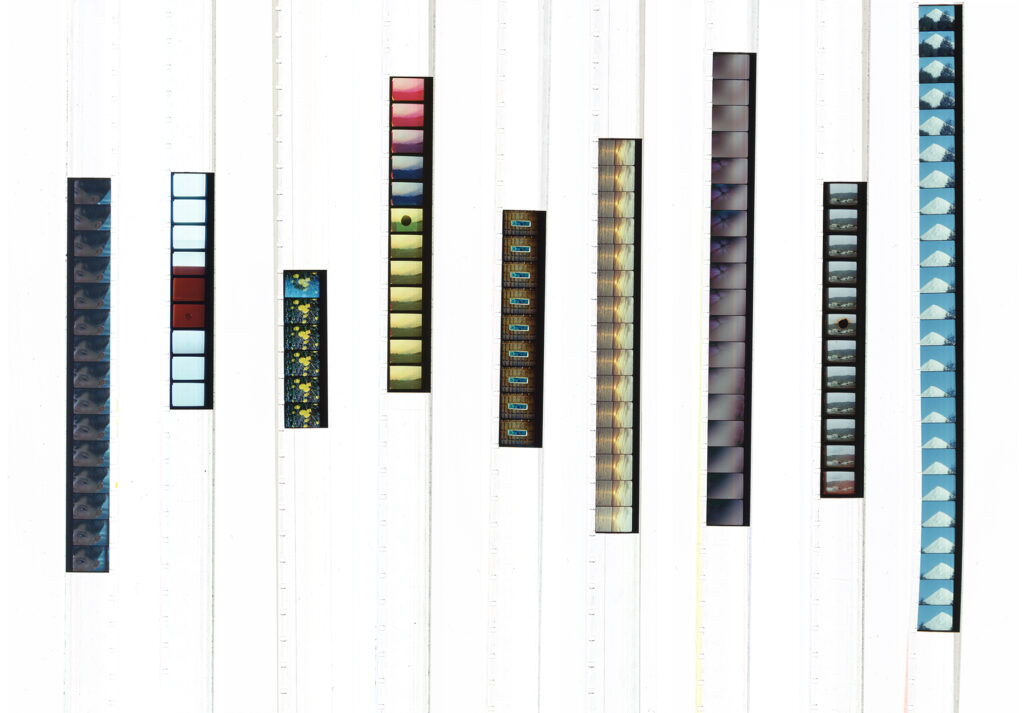

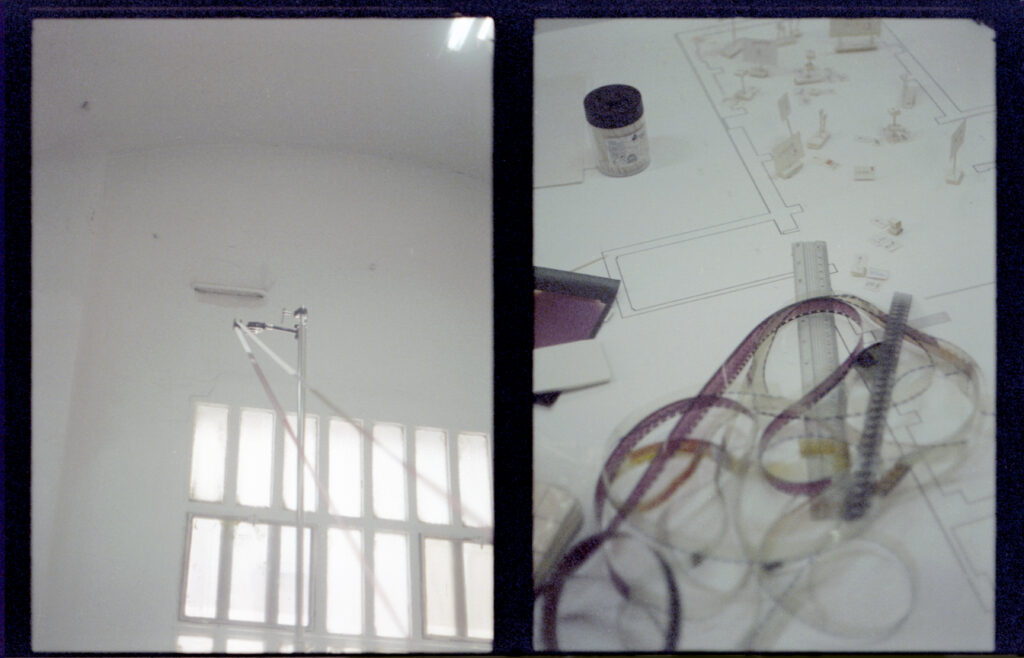

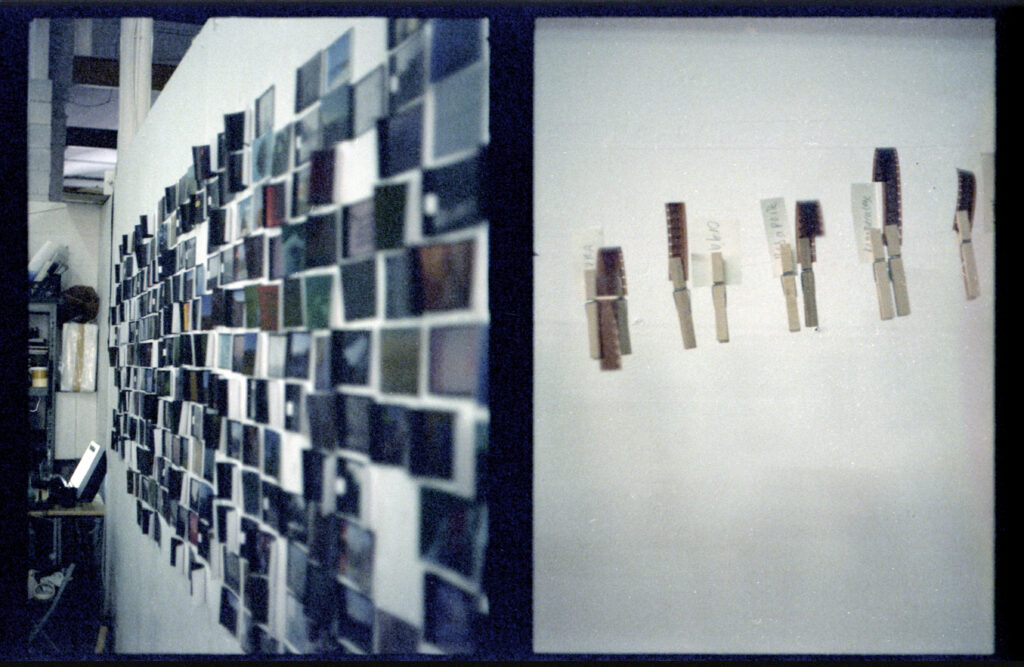

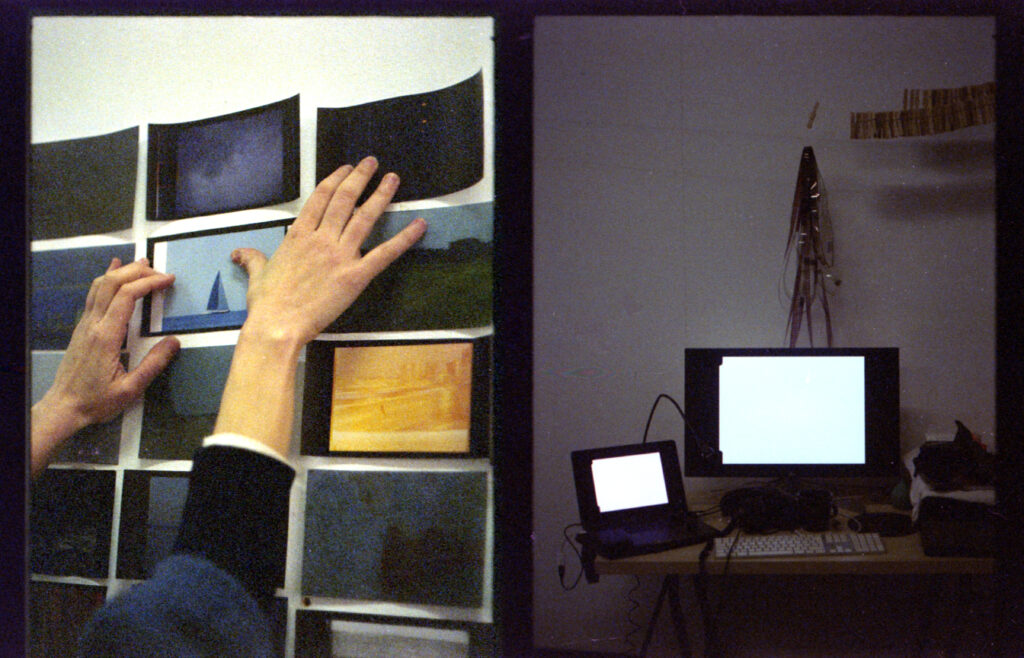

In Valentina Alvarado Matos and Carlos Vásquez Méndez’s recent body of collaborative work, flashing images appear from sixteen screens installed in the dark and vast expanse of La Capella in Barcelona—a contemporary art space that resides in the chapel of a former hospital in the borough of El Raval. Titled el otro aquí, which literally translates from Spanish as “the other here”, Alvarado Matos and Vásquez Mendez’s installation brings together rushes of footage taken over the course of a decade between Spain, Venezuela and Chile as part of each of the filmmaker’s personal archive, most of them shown in this work for the first time. Their studio residency at Hangar in Barcelona has allowed the artists to revisit this individual material as a collective endeavour. When I visited them in January this year, hundreds of small, printed images occupied their walls, creating a mosaic of portals into the worlds of their films, travels and personal encounters. For the exhibition, the rushes have been edited into segments that are almost as still-like. Allowing them to appear only for a matter of seconds on each screen in a non-synchronised choreography, Alvarado Matos and Vásquez Mendez’s installation creates a visual perspective that could be somewhat associated to the phenomenon of the life review. However, by refusing to narrativize the experiences embedded within these visual documents of their lives, and instead presenting literal fragments of often mundane and de-contextualised scenes, the filmmakers have devised a work that obfuscates film’s propensity to enforce a form of capture; of a moment, a place, a memory, or indeed a life.

The resulting environment immersers viewers in the appearance and disappearance of images, with the in-between moments filled by the light emitted from the various projectors installed in the room. As filmmakers who shoot almost exclusively on celluloid and who are concerned with the materiality of film, the rushes feel less like the discarded elements of their works—a surplus to the requirement of an edit—and more like autonomous images, each made in their own right. Even if they are disconnected from their original contexts, or if they have been used in previous works, these images appear to be free, here creating their own meanings. It is in no small part for this reason that it’s easy to find oneself completely involved in these flashing moments as they come and go. Though the impulse may be to try and keep track of everything that can be seen, what becomes more compelling is to realise what exactly remains in the mind from what we see. And thus, it is of no surprise to find that what one person vividly recalls, someone else might have totally ignored—and what becomes significant to one visitor, might have been totally unremarkable to another.

As an aid to our imagination and our ability to remember, the blank space that is edited in between the images not only buys us time, it also points our attention to what we may not have noticed otherwise. Indeed, we need not look for long to start picking up obsessions and repetitions that emerge from each of the filmmaker’s ways of seeing the world. Hands that piece together a broken vase, that are being washed after working clay, that roll dough in between palms, that draw, that paint, that hold… one could assume all these hands belong to the rushes of Alvarado Matos, who has for some time been concerned with the ways that the materiality of film and ceramics allows her to explore tactility and sensuality through the image. Conversely, the role of the artist as a historian emerges throughout Vásquez Mendez’s work, and as such we may find him surveying a myriad of landscapes: faraway mountains, a volcano range, a tree, birds overlooking a plain terrain, or a barren track. Whether or not these images are intelligible as being from one filmmaker or another is beside the point, and this is a testament to their collaborative practice. The devised filmic choreography importantly does not require a symbiosis of their archives; it allows both artists to come forth with their own subjectivity, and for us to be affected by each of them in return.

What Alvarado Matos and Vásquez Mendez’s subjectivities do share is a desire to convey the memories of a place of ‘origin’ as something that is rooted to a sense of home that is simultaneously here and there. el otro aquí makes an emphasis on “other” in relation to somewhere else rather than someone else, and on “here” as a place that is both particular and nondescript. That we mostly don’t recognise whether these rushes come from Spain, or Chile, or Venezuela, or elsewhere, importantly counters the expectations that are often forced upon migrants to make sense of where they come from to others. By sharing the affective, relational and physical connections that they have formed in all these places, Alvarado Matos and Vásquez Mendez’s work poetically renegotiates the notion of belonging as something that ever reaches an end, to be rather a feeling that is in a constant process of arrival.