A Moving Canvas

by Vera Martín Zelich

Milena Rossignoli and I met up a couple of times at her studio at Hangar, where she was working on pieces for her upcoming exhibition, even before I was invited to write about her work. Those initial visits marked the start of a dialogue through exchanges, references, and images, culminating in this article. Rather than a chronological or thematic journey through her work, the aim in bringing together this material is to explore the connections between mediums, materials, sensations and spaces. To add something new to the mix.1

My first encounter with her works was at Raccoon.2 Even then, I found myself wondering about the role of movement and displacement in her art, how they might shape her process. Many of her installations possess a latent potency of movement inherent in their form. For years now, Milena has practiced Aikido daily; this Japanese martial art is centred on falling, the timing of movements and breathing. The practice has influenced her work in such a way that her relationship with materials is expressed through a bodily, kinetic language that she is continually learning over time.

The pieces she has created in recent years are expansive, sprawling. Despite their large scale, it is important to her to manipulate and move them unaided. This was the case with Ukemi Ushiro Ukemi ,3 where she experiments with forms of falling through her encounters with materials of varying technical resistance, which she stretches, bends and tightens.

Ukemi Ushiro Ukemi, Generación 2024, La Casa Encendida.

I think it’s a form of control; if I can handle the piece with just my body, I can work on it. But it also limits my ability to receive help. Generally, I prefer to work alone, mainly because I don’t feel comfortable directing others. For me, sculpture is a solitary process, although I’m exploring other avenues.

When it comes to form… there are certain intuitions I pursue. I’d call them sensations of form. It’s the material itself that conveys those sensations to me. Then the work lies in discovering how, from nothing, I can arrive at that intuited form. Repeating, failing and repeating until I grasp that nothingness. Until I understand and handle the material in a certain way. The form I strive towards is the moment when the sculpture becomes self-supporting and no longer needs me.4

For this interplay with form to occur, she has to enter into a particular state with the pieces and materials in the studio—a relationship untethered to the need to solve or respond to anything specific. Here, the relationship with time also expands.

The work involves staying in a state, I don’t know if it’s a state of mind, if it’s mind or body. Staying open, receptive. You can’t define that state because it disappears as soon as you try. This only happens when I’m alone. If someone is with me, they have to be in that same state; if not, it becomes something else entirely.

In an interview, artist Gedi Sibony5 explains the frustration he feels not being able to make a sculpture levitate. But he notes that what he does achieve is making it support itself, exist independently. It’s about accepting things as they come and working from there. Rather than a question of accidents or coincidences, it is a desire to explore what you have at hand. I find a kinship in the way both Milena and Gedi pause to observe the consistencies of materials, what they contain and can contain – their history, their different past and future uses. In Milena’s case, the choice of materials is no accident and has a great deal to do with their weight, elasticity and how much they can change shape; materials with memory, but from which the gestures of what has been done can also be erased. Cement, technical fabrics and carbon rods are highly susceptible to changing use and form because they already possess that multifunctional ability to construct, join and protect.

I have several memories from when I was little, and we’d go to the mountains with my father. He always carried a backpack where he kept a paraglider. When we got to the top, we’d help him unpack it and set it up. Then my father would fly down with his paraglider, and we’d meet up at the bottom of the mountain. The lightness of the fabric, the power to open up to something so big that it turns into an object that lets you fly, that’s something that stuck with me. It was perceiving space, dimensions, the material interacting with the wind.

In 2021, Milena presented Trikini at Océanomar6, unveiling a piece made with a piece of fluorescent green fabric from her father’s paraglider, which is set in motion by a person in movement. The fabric adapts to the body through the cords, and the wind makes it change shape. It is a moving canvas. In the words of Alex Palacín, who stood inside the piece: “A uniform and stable force began to dance with me, and suddenly walking became a two-way matter. I tried to meet Mile’s eyes to convey my surprise and joy, but when I saw her, she was engrossed in looking at a kite”.7

https://www.instagram.com/p/CwFLmqWKGSR/

The colours of her sculptures tend to be neutral: greys, browns, pinks. Once, Milena told me that she didn’t dwell too much on this aspect of her work and that the variation in tones simply came about through the material’s own journey, its affections: light, opacity, the wear and tear of the surface.

Finding other colours in her work is unusual. When she does open to a wider palette, she goes in one of two directions. One is when the choice of a particular fabric or medium already comes in that colour, like it does with Trikini or Decollo. Other times, she expands her colour choice after observing a material’s qualities, its potential for variation and reaction to other agents. For example, part of her process with concrete involved applying a paint that reacts with it in a certain way. When I decided to ‘paint’ the concrete I used an ink that graffiti artists use because it’s very black and contains aniline, the ‘Nero d’Inferno’. The aniline causes a chemical reaction when you try to remove the paint and the colour changes to a reddish tone with oily reflections like gasoline. I’ve used this pure aniline highly diluted to dye fabrics; some of them are the pink fabrics you’ve seen in my studio.

Decollo, 2019.

Practice, 2020.

Craig Green is a fashion designer whom Milena feels a strong connection to through his choice and use of materials. These are technical fabrics that allow him an agile interplay with form, while other elements like rods, fringes or cords offer a certain type of movement and consistency. In an interview, Green notes that during the process of creating a garment, even from the earliest stages, he likes to see it in motion; even before choosing the fabrics, he simply hangs up paper in the colours he wants to work with on the wall to see how they interact, what rhythm they generate.

Craig Green, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSfbo9F90e0&ab_channel=fashionvideos

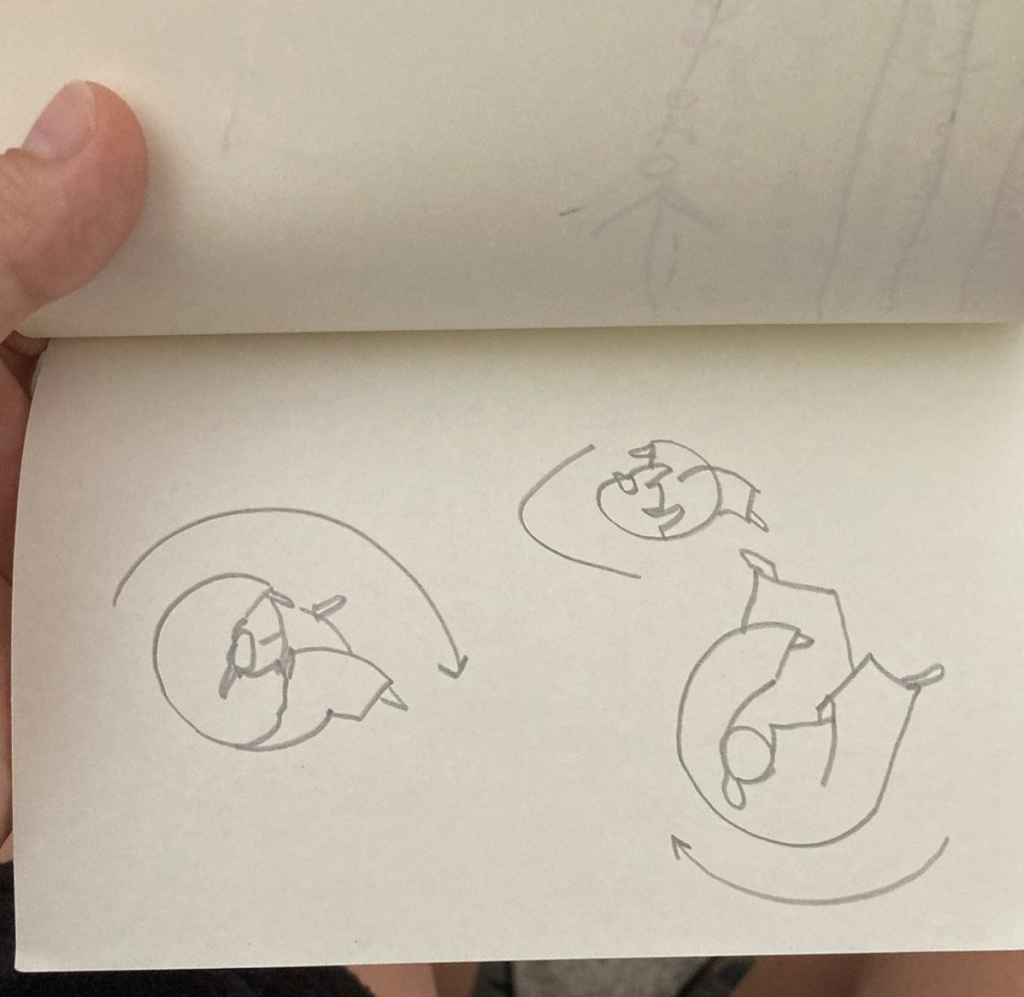

The two central pieces in IRA elevare per impeto violento explore a gesture that first emerged in an earlier work, Labena. Labena grew from a semicircular fold that was created while the artist was experimenting with the positions of a fabric. Once that fold appeared, the urge to sustain it and amplify that gesture by focusing on the line and movement took shape. This produced Labena, which then expanded into the two pieces of IRA, in which she continues with the initial form but adds two steps, two moments, as if a powerful gust of wind had blown in and lifted the sculpture. To identify that first fold and stretch it into a form that can develop and transform is, ultimately, to recognise something immensely subtle, like a vibration8, and to work from that impulse.

IRA elevare per impeto violento, 2022.

Labena, 2022.

This group of sculptures is crafted from light, accessible materials that Milena uses recurrently: cotton fabric, fibreglass, thread and carbon rods. She has moved cities and studios frequently in recent years, so the materials she chooses to work with are collapsible, reusable and easy to transport. I think both these experiments and the need for light weight—to move work effortlessly and without damage—steered me towards pursuing lightness. That’s why I started using lighter fabrics. By folding them and leaving the creases, I ended up incorporating that as part of the process. Another reason is the malleability these materials offer to enter into a continuous state of testing and dialogue with them. They allow to make and unmake, to think about the gesture in motion and anchor it.

Laurence Louppe9 reminds us that the object reveals the gestures it contains, the latent gesturality of its own manufacture and manipulation. Milena’s proposals manifest this direct relationship between object and corporeal memory. Recently, she has developed a series of works pieces that draw inspiration from the proportions of the tatami mat used in Aikido to cushion falls. These flat, outstretched pieces become supplementary studio surfaces that she can move and work on. The basis of Ukemi Ushiro Ukemi is the surface where, over weeks, she was creating the rest of the structure.

Tatami, 2018

Studio at Hangar, 2024

Fall, weight, ground meet in her work. Together, these three elements interact in continuous flow, tracing ascendant and descendent vectors, a tensile thread that tightens and releases. Both Aikido and dance are kinetic arts where weight, motion, gravity, falling are core actions and factors of a language marked by gesture. Louppe places the fall, as part of movement, in that liberation that happens when the body’s weight is driven by its own propensity, the floor a surface of rebound and transport. By virtually transposing the tatami into her studio, Milena maps a space where the cadenced codes of her Aikido practice reverberate, materialising in these newest pieces.

- As I came closer to completing this article, I met Milena at the dojo10 after her morning and we walked together to Hangar, where she showed me her latest work. Lines inscribing space as though arresting movement across multiple planes. These new pieces remind me of earlier works like Dirección vapor, where wood bent by wafting steam emerged from the wall, as if connecting the space through delicate spatial gestures. And underfoot, a fresh terrain: she’s started to use a new fabric as a base from which to work. It looks like paper, right?

- In the closing text of Anthony Huberman’s Abbas to Yuki. Writing Alongside Exhibitions published by The Wattis Institute (2019), the author writes about the potential approaches and ways to talk about an exhibition or an artist’s practice “…but it’s also about contributing an insight or two that adds something new to the mix”.

- In September 2022, she exhibited IRA elevare per impeto violento at Raccoon, an independent exhibition venue in Hospitalet, Barcelona, and directed by Margot Cuevas.

- Ukemi Ushiro Ukemi means Falling Forward, Falling Backward. This installation was presented in the Generación 2024 exhibition at La Casa Encendida, Madrid.

- Italic text written in the first person are excerpts from conversations with Milena.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GZPpuoPR5Q&ab_channel=SculptureCenter

- In the summer of 2021, Mónica Planes, Alex Palacín and Margot Cuevas put on Oceánomar, a one-day performative collective work at the beach, with participation from Álvaro Chior, Maria Diez, Anna Dot, Sofía Montenegro, Milena Rossignoli, Marcel Rubio, Anna Irina Russell, Alba Sanmartí, Anna Sevilla and Cristina Spinelli.

- Excerpt from the personal writings of Alex Palacín. 2021.

- “A fabric is a disturbance, a change in tension, a change in energy. A fabric is a vibration or millions and trillions of vibrations. / The world is made of vibrations”. Gilles Deleuze. Cine I. Bergson y las imágenes, Cactus, Buenos Aires, 2009.

- Laurence Louppe was a French author who specialised in aesthetics and dance. Poética de la danza contemporánea. Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, 2010.

- A dojo is a place for practicing martial arts.