carmine parasite

by Laura Vallés Vílchez

Marta Velasco-Velasco, frame from Mengikat llengües (Tongue Mengikat), 2023.

Sami sami is playing when I receive the invitation to write for this new editorial space that Hangar is opening: the ‘breaths’ of Elvira Espejo Ayca. Elvira is the first person who comes to mind when I think about exploring the wealth of knowledge on weaving, the colonial entanglements of weaving processes, and—as in the case of the mengikat presented by the resident of this Barcelona space managed by women I admire—when I ponder this “think-with” Marta Velasco-Velasco. That’s why I accepted this invitation, despite these times of collapse and exhaustion, when pausing to write is increasingly a luxury for those of us fortunate enough to have a shared creative practice.

So, let’s begin with a proposal. Let’s take a step back: I’ve inserted a link. Press play. From this window, I invite you to pause for a moment and listen to Elvira sing her ‘breaths’:

Phaxsi sami

Wara wara sami

Wayra sami

Uraq sami

Phaqar sami

Jumas naya layku

Nayasay jumas layku

Mapitay irpasiñani

Sami sami samiBreath of the sun

Breath of the moon

Breath of the stars

Breath of the wind

Breath of the earth

Breath of the flowers

You for mei

And I for you

We will carry each other

Breath, breath, breath

In this now lost communal ceremony, women carried candlesticks, men carried fire wrapped in ashes, and children carried water in pitchers, along with green leaves and flowers. They climbed the hill singing, a popular practice that, thanks to her grandmother’s stories, Elvira has revived in her discography.

My conversations with this Bolivian artist over the years stem from a sustained interest in the Principio Potosí (Potosí Principle) exhibition at the MNCARS in 2010; Elvira Espejo Ayca was a participant. Through these exchanges, I’ve reflected on many contemporary concerns about curating and cultural policies. Her artistic practice, not only as a weaver, narrator of Aymara and Quechua oral traditions, and poet, but also as director of the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, has helped me understand the contradictions and complexities of representation politics that shape today’s landscape. It’s also shown me what can be done from artistic and curatorial perspectives to foster global coexistence when the drums of war are sounding.

How can we imagine ourselves beyond the antagonism and violence that repeatedly establish themselves in all spheres of communal life? How can we overcome binarisms (reason and sensibility, art and science, subject and object) and inhabit an in-between space, a middle? We must be aware that, as Espejo writes, “people who study do not weave, they don’t know about praxis, they only look and describe with their eyes. Academia stopped at a superficial description”1. It’s urgent, as Teresa Lanceta would say, “to look out of the corner of our eye, to look askance”2, so that theory and practice can weave together an ethics of world knowledge.

Let’s pause for a moment here to leave the Bolivian Andes and journey to another “middle”: the Middle Atlas mountains of Morocco.

IVAM brought Elvira Espejo and Teresa Lanceta together for a chat at the Pensar con las manos (Thinking with Our Hands) event, blending the transnational pedagogical efforts of the Articulacions study programme with the teachings from Lanceta’s Tejer como código Abierto (Weaving as Open Code) exhibition. Teresa reflected on weaving as “technical” knowledge – a téchne dependent on specific geographical, cultural, and human contexts. She explored the concept by immersing herself in the world of the Aït Ouarain women, whom she visited regularly for three decades in the mountains that stretch from Morocco’s southwest to northwest. “You don’t buy the hours”, she told herself after pondering a carpet’s impermanence, drawing attention to the ways that tourism has disrupted the timelines and essence of weaving across non-Western crafts. “You buy the soul”3, she added. Here, the soul is the force that pours from the space between weaver, weaving, and loom; a form of grasping and mediating that Espejo’s community calls luraña, the act of making, of creating.

Elvira defines this community weaving practice in the Bolivian Andes as women’s science and technology. Oral histories, community economies, and harmony with nature provide what she terms “mutual nurturing”, an education based on the mutual exchange of knowledge and feelings. This stems from frustration with Western universities and institutions of knowledge and their lack of recognition for their ways of life as institutions that remain rigidly pyramidal in their hierarchisation of knowledge, trapped in ocularcentrism.

Perhaps for this reason, Teresa Lanceta insists that writing most closely resembles her longing for flamenco, another art form she grew up with in Barcelona’s Raval after dropping out of university where she studied History. At the dawn of Spanish democracy, her textile politics defined her artistic practice, one that was sensitive to the migrant environment of a neighbourhood not yet transformed by today’s tourism. In “Entre alfombras y tejidos” (Between Rugs and Textiles), she recalls the migrant women who shaped her creative ethics and describes the yearning for a farewell:

When you left, I hugged the trees and pressed my face

against the trunk until I heard your voice and felt your breath.4

As if their looms were harps and their written words a voice, the stories of remembrance and loss for other ways of grasping, of knowing: the “breaths” of both women help us understand how one can listen with fingers, how hands feel as they recover and share knowledge incarnate. It’s from this intersection of intimate yet diverse positions that I delve into the materials accompanying this invitation to “think-with” Marta Velasco-Velasco, whose work I discover through this exchange.

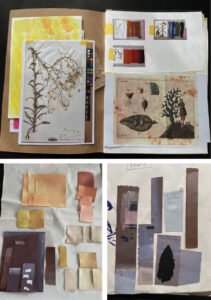

Marta Velasco-Velasco’s studio in Hangar, Barcelona, 2024.

In line with these textile genealogies, I sense that Velasco-Velasco also looks at things askance, out of the corner of her eye. In her work, subtle encounters between materials and identities emerge in an emotional, embodied way, rooted in traditional techniques that align with the desire to think with one’s hands. For years, Velasco-Velasco has focused on the flows of colonial bodies and capital that have unleashed a collective imagination whose consequences have led to global processes of acculturation and Euro-Americanization.

The exoticisation of material experiences, so relevant in a time when we are all tourists and idiots (to borrow from Fernando Estévez’s “Souvenir, souvenir”, our Bruno Latour), has served as a framework for exploring how to inhabit this in-between space, situating ourselves in the middle. Undoubtedly, culture’s natural condition is a state of flux, and the system of norms—set by academia’s superficial description—doesn’t truly exist as such. This is another failed attempt to lock something we might call culture into place; in reality, it is a constant, promiscuous, and perverse becoming/framework.

Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble and its “string game” evoke a consistently useful image for imagining this continuous reconfiguration of the framework from the techno-science of women who resist the descriptive, constrained, and ocularcentric character of much of academia. Following her time at Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art in London, Marta also classifies herself as part of that same academia. In an eponymous essay that contributes to the shared task of using feminist anti-racist theory and cultural studies to produce patterns of worldly interference, Donna draws on two threads to address the semiosis of the embodiment of “bodies that matter”. She attempts to track networks of configuring agency that might lead us to places different from “those reached by tracking actors through the networks of another game of war”5. This scientist believes that the practices of techno-science construct worlds that aren’t brimming with options for inhabiting them. Consequently, she aims to change specific normalised categories in favour of a hope for inhabitable worlds.

It is striking how these words, written three decades ago about the militarisation of techno-science, unfortunately remain relevant. The process of semiosis that Haraway discusses implies a three-way relationship between a sign, an object, and an interpreter. Before representation, the sign is pure potential. Could this be another way of naming the soul that Lanceta perceives pouring out from between the weaving, the loom, and the weavers? Is it like the luraña that Espejo experiences when art is executed with feet, hands, head, heart, and the entire body in a process of mutual nurturing?

This state of latency and the possibility of changing normalised categories seems to distil in Marta Velasco-Velasco’s materials, which reach my inbox as images. Fragments of fabric and paper dyed with natural pigments showcase a three-way relationship between plants, fabrics, and taxonomies, pointing towards the corporeality of more-than-human bodies that we now know also matter. These are vibrant materials, bearers of histories that challenge cultural flows and the rules that define systems of knowledge, sometimes lost when we are blind to their relevance. Marta asks herself how to appeal to the creation of alternative systems through plants. Her work shows us how territory at the floral level is defined by earlier uses of colour, with natural dyes offering other life experiences.

Six colours sourced from four plants picked on the roadside leading to Montjuïc mountain unveil a desire for both the future and the progress of old: pine bark, eucalyptus leaves and bark, the plague of wild cochineal on prickly pears and laurel. Pine and laurel are indigenous to the Mediterranean, while colonial processes brought cochineal from Mexico and eucalyptus came from Australia.

That said, Marta recounts how blue in Europe once came from the pastel plant (isatis tinctoria), which farmers stopped growing after indigo arrived from India. She also says that, before cochineal reached the peninsula from America, red was produced from a plant called madder. Spain led European red production, the Canary Islands playing a crucial role in this equation. The introduction of synthetic dyes in the late nineteenth century exponentially reduced technical knowledge of natural dyeing processes.

Today, pastel and madder are weeds that grow wild in ditches across the country. Cochineal, the parasitic insect used to colour lipstick, is also a plague on Montjuïc.

Elvira Espejo explains that cochineal without mordant yields a soft violet colour, considered the primary colour by dyers in her community. Adding citric acid as a mordant produces red, the secondary colour. More citric acid leads to orange. Changing the mordant to fermented tannins saturates the colour, turning it dark violet, almost blue.6

Colour is a science and technology conditioned by climatic changes. Plants in dry weather have brighter colours because they store more water in their leaves. Wetter weather results in less water content, and wind further affects the balance. Blue, for instance, depends on oxidation: more wind changes the colour, while less wind results in a weaker hue. In essence, the colour palette shifts through water immersion, managed in the Andes by the waraña muse: a colour designer who coordinates the palettes of different regions. Each weaver arranges colours on a stick by twisting the thread colours she wants for the piece to create her own colourway.

Interestingly, Elvira always notes that Western universal colour palettes go from lightest to darkest, following the teachings of Newton. However, in her communities, the waraña muse focuses on an unusual way of arranging colours, forms, and shades. This story comes to mind when I first see Velasco-Velasco’s tinted patchworks: initially sorted by brightness, then intermingled in a rod structure in a latter arrangement, as if to shift away from the linearity that imposes itself when those of us raised in RGB let our guard down. In this sense, the cartographies of colour of this small mountain in Barcelona that Velasco-Velasco presents remind us that “by losing the knowledge of how to create these colours with natural plants and minerals, we lose knowledge and ways of seeing the world”.7

Her particular waraña muse is another figure in the string game, helping us understand how taxonomies from over four centuries of history (hundreds of dried plant sheets collected in herbariums) fail to define a praxis, instead narrating a colonial market history. Indeed, they are negligent in their inability to narrate other forms of ritual, ceremony, and encouragement. “There’s a kind of transposition of relevance in these taxonomies that omits fundamental knowledge. For example, the madder root, which is what makes the dye, isn’t harvested”, Marta explains. This knowledge disappears from the record when synthetic dyes are imposed as cheaper options, subsuming colonial histories and leaving the narrative work of preserving “technical” knowledge, a téchne, in no man’s land. It is in this supposedly infertile place where artistic practice uniquely thrives.

Frames from the documentary Ciencia de las mujeres: experiencias de la cadena textil desde el Ayllu Mayor Qaqachaka, 2023.

Marta Velasco-Velasco, frame from Mengikat llengües, 2023.

Attentive to these stories of fading knowledge, it’s unsurprising that in her latest work, Mengikat Llengües (Tongue Mengikat) in 2023, Marta Velasco-Velasco mobilises the language of the delocalised subject and investigates the transmission of craftsmanship in the context of Mallorcan textile tradition. This project involving roba de llengües—a traditional Mallorcan fabric with patterns that look similar to tongues, made using the age-old ikat technique first practiced in Indonesia—takes shape as a twelve-minute film presenting the chain of operations that define the production of these vernacular fabrics on the island.

The term mengikat comes from the Malay word meaning ‘to tie, bind, knot or wrap’, referring to the knots tied in fabrics to prevent dye from touching the hidden parts. Through visual and material associations, Velasco-Velasco produces a film rich with divergent narrative layers, addressing the mestizo reality of a Mallorcan tradition not practiced elsewhere in Europe today. This makes it a valuable record of Espejo’s “mutual nurturing”. Thinking-with Marta about the network of natural/cultural flows in our recent histories, Elvira recounts how, in the 1930s, textiles from the Qaqachaka area were also worked simply with dyes, creating designs through tie-dyeing techniques like ikat or plangi in textiles, and q’awata in ceramics (also a form of ikat). Local people washed the threads, dyed them with the design, and then simply wove the fabric. In the Bolivian Andes, this tie-dyeing technique is called watasqa.

Marta Velasco-Velasco’s film reveals that an object-subject embodies the content of multiple actions, from the transformation of raw materials to the intervention of instruments, which she considers living machines because they contain all knowledge. It also explores the creation and social life of the object-subject and its role within its community. The sounds of the looms, the materials, and the relatives who continue this practice—teetering on the edge of aesthetic touristification—illustrate the impossibility of uniting the increasing multiplication, commercialisation, and falsification of fabrics for stark consumption. This consumerism unravels the intricate game of strings, mutual nurturing, and the construction of an ethical framework. It brings to mind Lanceta’s reflection:

The denial of the original function of objects and low prices break the unitary sense of work and time, weakening the entire social structure. The traditional chain of apprenticeship suffers and crafts are downgraded; with them the capacity for creation, quality and uniqueness.8

There is a moment in Velasco-Velasco’s film where she asserts that colour changes our imagination, reversing the process of negation. To me, this moment affirms the operational chain between weavers, weavings, and the loom. It is a process beginning with the theft of language and the renaming that spans from the Bolivian Andes and the Moroccan Middle Atlas to the Tramontana mountain range in the Balearic Islands, where the winds are dyed blue.

Thus, Mengikat Llengües (Tongue Mengikat) presents a technical tradition born from this flow, which we, looking askance, out of the corner of our eye, call culture. It underscores how our vision of the world is crafted from fragments that invite interpretation. Perhaps that is why it is so beautiful to write this text-textile based on scraps whose uncertain future is a breath within the patterns of worldly interference.

- Elvira Espejo Ayca in the Q&A after the screening of the documentary Ciencia de las mujeres: experiencias de la cadena textil desde el Ayllu Mayor Qaqachaka (Women’s Science: Experiences of the Textile Chain from the Ayllu Mayor Qaqachaka), 27 March 2024 at IVAM, Valencia.

- Teresa Lanceta in the Tejer como código abierto (Weaving as Open Source) catalogue, MACBA-IVAM Barcelona-Valencia, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Teresa Lanceta, “Rosas blancas” (White Roses), Adiós al rombo (Farewell to the Rhombus), Azkuna Zentroa-La Casa Encendida, Bilbao-Madrid, 2014.

- Donna Haraway, “A Game of Cat’s Cradle: Science Studies, Feminist Theory, Cultural Studies”, Configurations, 1994, 1: 59-71.

- Elvira Espejo Ayca, Yanak Uywaña. La crianza mutua de las artes, 2022.

- Conversation with the artist.

- Teresa Lanceta en conversación con Nuria Enguita, «El arte como código abierto», Concreta 02, Valencia, 2013.